From Mokpo to linguistics

I was born in Mokpo (목포), a harbor city in South Korea often called an “art city” (예향의 도시). It is known for its cultural tradition, sites tied to Korea’s modern history, and a strong food culture. People even talk about “Mokpo’s nine delicacies” (목포 9미). One local specialty is sebal nakji (세발낙지), baby octopus. In Mokpo, it is served extremely fresh, sometimes even raw, which says a lot about the city’s confidence in its seafood.

📷 View photo: Mokpo (목포)

Mokpo (목포), South Korea

Mokpo (목포), South Korea

Like many kids in Korea, I could have spent my afternoons in math and English hagwon (학원), private academies often described as “cram schools.” But my after-school life looked different. I practiced Korean calligraphy (서예), and I learned to play traditional wind instruments: the danso (단소), a short notched bamboo flute played vertically, and the daegeum (대금), a large transverse bamboo flute. I’m not particularly artistic, but I think my mother hoped these practices would teach me patience, focus, and a calm mind. Looking back, they also shaped how I value tradition and the quiet discipline that sustains it.

How I found linguistics

Later, I moved to Seoul and entered Kyung Hee University. I began college as a Physics major because I loved science and wanted to study fundamental questions. I was also drawn to big ideas, and I hoped my studies would connect naturally to philosophy.

Over time, I realized that I did not enjoy mathematical physics as much as I expected. Around the same time, I discovered something that felt just as systematic, but much closer to everyday life: grammar. I changed my major to English Language and Literature, and that decision led me to linguistics.

I became especially interested in syntax, the question of how grammar can be explained with clear principles. I loved the puzzle-solving side of language. As I studied more, I started paying attention to patterns that are less familiar or sometimes treated as “peripheral,” forms people use naturally even if they do not look like textbook examples. That curiosity led me to questions like these:

- Why do speakers choose one form over another?

- How do new patterns spread?

- How does language change become ordinary over time?

Research

I came to the United States to pursue my Ph.D. at the University of South Carolina. Here, I have been able to connect formal linguistic theory, language change, and sociolinguistics through training and collaboration.

In my dissertation, I examine how expressions change in structure and develop new functions over time. I focus on Korean and use corpus data from 1700 to 1990. Many theories of language change predict certain pathways of development, and many languages show similar patterns. I find that kind of systematicity fascinating. Based on this work, I argue that grammar constrains what kinds of changes are possible, while social and historical conditions shape when changes emerge, which forms spread, and which uses become conventional.

Teaching

In the U.S., I have also been fortunate to work as a Korean language instructor. In Korea, there is a saying that language reflects a country’s spirit. For me, learning a language should not be only about grammar. It should also include culture, history, and the experiences behind expressions.

When I teach Korean, I pay special attention to how Korean expressions carry cultural meaning, and I want my students to learn that too. One of my favorite parts of teaching is creating moments where students can feel the “older” layers of Korean culture. I sometimes hold a Korean calligraphy (서예) session, where students write Hangul slowly and carefully and discover how much meaning is carried in shape, spacing, and pacing. I also teach Korean folk songs (민요) like “Arirang.” Singing and reading the lyrics together becomes a natural way to practice pronunciation and intonation, while also learning why certain expressions carry a particular emotional texture.

Tools and why they matter to me

I am also enthusiastic about building a language learning tool for my students. My goal is to create something better than simple pattern drills: a tool where learners can understand structure, practice with guidance, and learn Korean in a culturally rich environment.

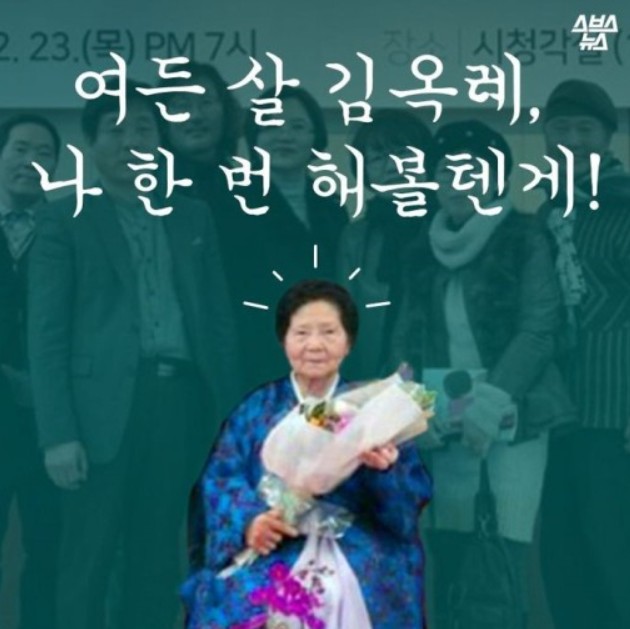

This work is personal to me. My grandmother (할머니) learned Hangul when she was almost in her 80s, and later she became a poet. When she was young, she did not have the opportunity to attend school, as many women of her generation did. Her story reminds me that learning is always possible, and that learning can open doors in unexpected ways. Even late in life, she found a new voice through literacy.

Today, with online learning everywhere and technology advancing rapidly, including AI, I want to build a tool that helps learners study Korean anytime and anywhere. I hope it can be clear, supportive, and encouraging for people who are starting from any point in their learning journey.

📷 View photo: My grandmother (할머니)

My grandmother (할머니)

My grandmother (할머니)

Later in life, her story and poetry were even featured on television, which made our family very proud.

🎥 Watch video: My grandmother (할머니)

A short clip featuring my grandmotherWhat I aim to do

Overall, my goal is to connect the structure of language with the people and histories that shape it, through research, teaching, and tools that help learners engage with Korean more deeply.

Other things that I love to do

I’m happiest with classic films and dramas, a good run, and a night of board games (or StarCraft). A few recent favorites: